![]()

Good morning; Oh, how humbled I am to be here. My name is Nicole Woodward, and my husband Joe and I have three beautiful children: Haddie, our six-year-old dreamer, Hazel, our two-year-old spitfire and Abel, who I like to imagine would be chasing his sisters from one end of this park to the other, and causing all sorts of mischief, if he were here with us today.

I have the honor of standing up here before you because I have loved, I have lost, and I am learning and living through it all.

If you’re here today, it’s because you, or your daughter or your son, your granddaughter or your niece, or maybe your friend or neighbor, have also loved, you have also endured an immeasurable loss and you have also experienced indescribable pain. And it isn’t just any pain, like that of a broken bone or of not making the team or not getting the job, no, this pain that I speak of is a deep, visceral, consuming, and quite possibly the worst kind of pain: it’s the kind of pain you suffer when your child dies. Perhaps you felt it when you were 6 weeks pregnant, when that life was so new it hardly felt real until it was gone. It might have come when you were 17 weeks pregnant and were supposed to be “in the clear” until you weren’t. Possibly this pain came at 5 months when everything happened much too early, or when your baby was inexplicably born still at 9 months after a completely uncomplicated and uneventful pregnancy. Perhaps, it was in those moments just after birth when complications arose.

Regardless of when it came, it came: this pain that is so severe and searing that it hollows you; leaves you feeling empty, grieving and hopeless, leaves you desperately longing for miracles and time machines. A pain that comes with such force that it reaches far beyond mother and father, it sends shock waves out from its epicenter and spreads throughout your village to all of your people; it gets carried by anyone who knows you and loves you.

And though not to the same degree, the people standing beside you today feel that pain too; they experience their own hollowing and we are all left with a missing piece where this baby should be.

For me, and for my village, that deep, visceral, hollowing pain came in waves. The first time I was hit by it, I was sitting at the kitchen table, 15 weeks pregnant with our second child, when I got the phone call that would change our lives forever. Our test results were back and in three seconds it was revealed to me that we would have a son, but that he would not live to see his first birthday, if he even survived to his due date or through his birth.

Trisomy 18, I was told, was a diagnosis incompatible with life and it had grabbed hold of every one of our son’s cells. A random third copy of his 18th chromosome would steal our son’s life and every dream we had already dreamt for it. As the words hit my ears, my toes curled in agony, I clenched the table in desperation, I bellowed from a depth reserved for things unimaginable. My husband came home and met me in that space and we sat there together, crying and aching; full of dread and uncertainty while we tried to figure out how we would survive what was to come. Recalling it now, it felt more like a pain tsunami than a wave; I will never forget how it engulfed me.

I’m sure you can relate, that you too were in that place, that place where the reality of the loss that has been suffered or the loss that is to come hits and everything gets knocked off kilter, and you’re left wondering if the world will ever get righted again.

The next several months were a blur; navigating this precarious pregnancy and hoping beyond hope that our son would be an exception to the Trisomy 18 rule. There was nothing that could be done to intervene, there is no cure, so we did what we could: we loved him, cared for him, named him; I carried him to the best of my ability. And our boy, our wee but mighty Abel, turned out to be quite the fighter: he fought through the entire 9 months of pregnancy; he fought through labor, and through delivery and then he fought to stay.

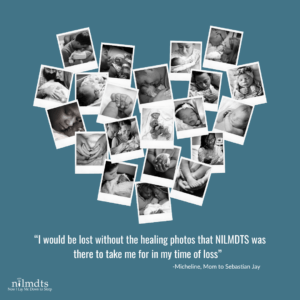

Abel was born living at 8:04 a.m. on February 19th, 2016, and he came into this world with the faintest but sweetest little cry I ever did hear. Oh how we grasped at every moment he gave us: we created every memory, captured every piece of him we could. We surrounded Abel with friends and family, and my dear friend and our incredible NILMDTS photographer both took the most gorgeous photos. We learned his face, we inhaled him and memorized him, we made sure he felt every ounce of love and security we had to give. But these moments were fleeting, and this coveted time with him, though a gift, was entirely too short. Abel fought and fought; he fought until he couldn’t fight anymore, and at 12:15 p.m., after a mere but miraculous four hours and 11 minutes of life, Abel took his last breath and died wrapped tightly in my arms.

I couldn’t bear saying goodbye to him the same day we said hello, so we spent that night holding Abel and loving him. We stayed with him the entire next day and soaked up every single bit of him we could until we finally had to face what we had been dreading my entire pregnancy: it was time for him to go and I couldn’t go with him. That’s when it really takes root, the pain; when it burrows into your bones and takes up residence in your soul. I was certain, in those most painful moments, that if I stood and looked in a mirror, I would see straight through my chest to the other side, via the Abel-shaped hole that had formed directly over my heart. And eventually I did stand, and I did look, but the hole, the hole with its sharp edges and infinite depth could not be seen. Physically I bore no obvious wounds, as all of the brokenness was reserved for my spirit, for my soul. There was nothing more our medical team could do, so it was time to go home, and while I knew it was time, my legs were like anchors, attempting to hold me steadfast and prevent me from drifting away from the place that contained Abel’s entire brief and beautiful life. My legs just would not carry me, so my husband lovingly wheeled me out of the hospital, flanked on either side by my parents and best friend, and I left: empty arms and an empty shell of myself, head buried in my hands, completely unsure of how I could possibly go on or how I would ever feel joy again. Another wave and I came crashing down.

I went home and I grieved. My body was screaming to mother but my son was not there to receive any mothering, and the pain of his absence was excruciating and altering. My mind was no longer sharp, my body felt foreign and fallible, and the Earth seemed to rotate on a completely different axis than it had before. I struggled to find my place, to plug back into my life as I’d known it before, and it devastated me that Abel, though such a palpable presence for me, was completely invisible to the rest of the world.

I shut out the sun: it was too bright, I couldn’t turn on the TV: it was too agitating, I stayed inside, because the outside world moved too fast; I sought quiet. I found a spot on the couch and I stayed there, wrapped in any comfort I could find, and I grieved. I mustered the energy to parent our daughter when I could, but more than anything I longed for the stillness and gentleness of my grieving space.

Have you been there? Did those early days of grief look something like this for you? Did you struggle to step out? Did you feel like you would never be able to find your place back in the life you lived before? Did you find it difficult to reconnect? Did you long for your child to be seen? Were you desperate for your baby to be visible to the world around you? Are you still there? Whether your experience was similar or different from mine, it was your grief and it was the right way to grieve. If there is one thing I’ve learned along the way, it’s that though there are certainly common experiences, everyone grieves differently and there is absolutely no right or wrong way to do those days, weeks, months or years after your baby dies.

But then what do you do from there? How do you get back to living? How do you create a new normal from this altered state? I’m not sure if it was even conscious at first, but after some time I felt like there was a choice to be made: I could sit in that hollowed space, stay in that emptiness of grief and let it swallow me whole, or, I could begin filling it up. I could fill it up by findings ways to mother Abel even though he wasn’t physically here, so that’s what I started to do. I made space and began filling the hole that Abel left behind. It started small, with a framed picture of him placed on the mantle, and the amount of peace I felt from seeing his face in the center of our living space was so great that I kept going: one picture turned to two and two pictures turned into memorial shelves filled with gifts given in his honor. We hung a chime in the backyard so we could hear him when our daughter played outside, we made a playlist of his songs, we started seeing him in rainbows and sundogs in the sky, and I got his name tattooed on my arm. I wrote about him and shared posts for anyone who would read them.

I pulled all the pieces of him I could to the forefront and I made him as visible as possible. It’s what I had to do to move forward, to survive; it’s what Abel’s Dad needed to find a place for his grief, it’s what Abel’s big sister needed to stay connected to the memory of her baby brother, and it’s how we’ll introduce Abel to his little sister when she’s ready.

Making space for Abel in the nooks and crannies of our home and our life gave me the courage I needed to step out into the world, to open the curtains and let the light back in…

Create space. Fill it up. Honor. Heal. It’s what we all do, what us mothers and fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers, aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, friends do: we make space for the babies we have lost, because they can’t make their own in the ways a living child does. We make the space and then we start to fill it. We fill the space with symbols and stories. We fill it with photos and memorial gardens. We fill it with tattoos that bear their names and with organizations formed in their honor. We fill it with shrines in the corners of our homes and in our hearts with mementos big and small. We fill it privately and publicly. We fill it by creating networks of support with others who have also loved, who have also suffered unimaginable loss and who are also trying to figure out how to live with it all.

We take that painful place and we use it. We fill the space; and in doing so, we make our babies who are invisible to the world, visible- visible to us and our families, visible to our friends and neighbors, visible to people we meet in our day-to-day lives. We create space, we fill the space and we fill that gaping hole, we honor our babies, and we start to heal.

Create space. Fill it up. Honor. Heal.

We are carried by these tiny spirits, these little legacies who make the most enormous impact on their mothers and fathers and who have made an enormous impact on each and every person who walks alongside those grieving parents every day. Take a look around you. Who else is carrying your son or daughter? Who else is remembering them and seeing rainbows as signs that your baby is near? Who else is hearing your precious baby boy or girl in a song or seeing them in a cardinal or in sunbeams shining through clouds in the sky? Who else knows your child, loves your child and says their name? I see my people; I see all the amazing ways they show their love for Abel, and it means everything to me. Whoever your people are and however they’re doing it, It’s because of you. It’s because of you and how you’ve filled up that hole. It’s because you’ve mothered or fathered that beautiful life in beautiful ways that are true to you. It’s not because you stopped – or will ever stop – grieving, but because you have been brave in that grief, you have taken your pain and turned it into purpose.

And maybe you are in that hollowed space right now, maybe you are grieving so deeply and freshly that you can’t even begin to imagine how you would start filling up that hole; maybe you don’t know how, or you feel alone, or you are weary from loss. Hear me when I say that it’s ok. It’s okay not to be okay, it’s okay to be struggling and to not know how you’re going to find joy again. It’s ok to not know what you’re going to do next. You are here, you are here and you are not alone, know that there are people who will help fill you up, who will get to know and get to love your baby and who will say his or her name with honor and compassion.

When you hear your baby’s name here today, let the song of it dance in your ears, let it sit on your heart, and, if you’d like to share your story with someone here you can share it with me, I’m listening; I see you and I see them.

Just by being here today, you have made space. Just by having your baby’s name on this roster, or releasing a butterfly, or donning the t-shirt or walking the course, you have filled the space; you have honored your child, and hopefully in doing so you find even the smallest amount of healing.

Create space. Fill it up. Honor. Heal.

It’s been almost four years since those waves of loss crashed into our family. I feel like I’m just starting to really get my feet back on solid ground and I’m still creating space for Abel, still filling up the hole, still mothering him in the ways I can; I’m still grieving. It’s work I’m sure will never be done and I’m certain will look differently as the years go on, but it’s good work and I’ll do it for Abel forever. I’ll honor him this way for always and in the process continue healing the hurt. I’m so grateful for you listening this morning, for allowing me this space and for letting Abel’s name and his story sit on your hearts, even if just for a moment: It has filled the hole and brought me incredible joy. Now the next minute, hour, day, week, month, year…they are yours. Yours to create space. Yours to fill. Yours to honor. Yours to heal. There is so much room in this beautiful world for your beautiful babies.

Thank you.

![]()

Sad, beautiful, remembering words that touch the space in our hearts….a place that our great grandson Benjamin James ccupies every minute! Honoring and loving forever his precious, dear life (almost full term, stillborn). Our granddaughter, her husband, their adored rainbow baby, Emily Victoria, family, and friends continue on with appreciation for each day! Blessings to you and your family.